Bishop Patteson - The First Bishop Of Melanesia

Bishop Patteson was an Englishman who responded to the call to work as a missionary in Melanesia. His story shows the courage and resolution of the human spirit.

Jane RestureNov 08, 2023164 Shares27395 Views

His father, Sir John Patteson (1790-1861), was a lawyer of no mean repute, who was raised to the position of judge in the year 1830. Wherever he traveled on circuit, he gained respect and made many friends.

To the very end of his days, his boy loved him with unfailing loyalty and was always ready to acknowledge, with heartfelt thankfulness, how much of what was best in him was due to that honored parent whose name he bore.

From his father, Patteson inherited that sturdy backbone of principle and straightforward bravery.

This courageousness stood him in good stead in the history of his school life and the heroism of his later years.

Early Influence

Yet, to complete the character of Patteson, it needed another influence, and that was supplied by his mother’s gentle love.

It is so true to human nature that it will cause no surprise to add that the boy partook largely of his mother’s intellect.

An infinitely strong link of mutual love and confidence connects them together, which water cannot quench nor fire can consume.

Her mother, Frances Duke Coleridge (1796-1842), belonged to the same line of ancestry as the poet, philosopher, and literary critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834).

To the future bishop, she gave her family name, and amongst those who knew him best, not only as a boy but also afterwards as an adult, he was known as “Coley.”

There were two other strong influences that directed the heart of the boy in the direction of Christian mission.

One of them was Bishop George Augustus Selwyn (1809-1878), New Zealand’s first Anglican bishop.

The other was the Reverend Samuel Wilberforce (1805-1873), a notable Church prelate, who served as Archdeacon of Surrey.

Education And Her Mother’s Death

Patteson attended Eton College.

While studying there, for some time, his mother, Lady Patteson, had been ill. Suddenly, graver symptoms summoned hastily the judge to her bedside.

Lady Patteson called her family to her bed to say farewell, caressing and blessing her sobbing boys.

Then, throwing her arms around the neck of her husband, she thanked him for bringing them to receive her last embrace. Shortly afterwards, she died in her sleep.

In 1845, Patteson entered Balliol College.

He came at once into contact with that remarkable quickening of religious thought, which will mark an epoch in the history of the Church of England.

All the self-examination Patteson subjected himself into had stimulated him, and he developed a clearer assurance of duty.

He made friends with people with earnest minds. Some of those who survived him have recorded Patteson’s affectionate and interesting memories.

One of these is the testimony of Professor John Campbell Shairp (1819-1885), of which the following is an extract:

“„Patteson, as he was at Oxford, comes back to me as the representative of the very best kind of Etonian, with much good that he had got from Eton, with something better not to be got at Eton or any other school.- Prof. John Campbell Shairp (1819-1885)

Professor Shairp continued:

“„We did not know, probably he did not know himself, the fire of devotion that lay within him, but that was soon to kindle and make him what he afterwards became.- Prof. John Campbell Shairp (1819-1885)

Early Travels

After three years at Oxford, having secured a second class in Literae Humaniores(humanities) - refers to Classics at Oxford University - Patteson set out for a much-needed holiday on the continent.

He traveled through France and Germany, where he found his French and German to be of practical use when he left for a time the English shores.

When Patteson was in Venice, he received a letter from his father saying that he had decided to resign from his judicial duty. He had been a judge for 22 years.

At the age of 62, his father still had plenty of years ahead of him as a judge, and the prospect of him leaving the court for good was a regret to all.

Patteson, returning from his journeys, became a Fellow of Merton College in Oxford and threw himself with zeal into the movement for reforming the University, which, at that time, was in progress.

The time approached, however, when Patteson had to leave the towers and spires of Oxford behind. With redoubtable zeal, he worked away at his books in his room at Merton College.

At this time, a providential door opened, by which Patteson was able, at once, to taste the sweet joy of real parish work.

Ministerial Work

Within the Ottery St. Mary Parish Church lies the village of Alfington.

The church, parsonage, and premises were a gift of the Coleridge family, and it was intended that Patteson should one day occupy the pulpit.

In the meantime, however, Reverend Henry Gardiner, who was working in the parish, was struck down with a severe illness.

In 1853, Patteson arrived to nurse him and at the same time to assist in carrying on the work in his absence.

He discharged both duties with faithfulness.

On September 14, 1853, Patteson was ordained at St. James’ and St. Anne’s Church in Alfington.

He experienced both the joy and the sorrow of working at the ministerial office.

In August 1854, Bishop Selwyn and his noble wife returned to New Zealand to give an account of his stewardship.

The Church In Melanesia

The development of the Church in Melanesia was greatly hindered by the endless subdivisions of dialects.

Therefore, Pattenson devised a plan to induce the natives to leave their homes in the islands and undergo a course of instruction to make them fit for Christian work.

In a quest for help, Bishop Selwyn revisited England again and approached Patteson for help.

At the dock at Blackwall Yard, the new Melanesian Mission schooner, the Southern Cross, was being constructed.

Patteson spent some days in London preparing his requisites for the voyage. It wasn’t until the 25th March that he was finally able to say “Goodbye.”

The Voyage To New Zealand

On the deck of the Duke of Portland, which was to bear him away, Patteson parted with his uncle and his brother, James, and was soon on his voyage to New Zealand.

Two things made Patteson busy on the way.

First, he attempted to master the Maori language. Second, he studied the practice of navigation.

In the former, Patteson was most successful, and in the latter, he showed an equal proficiency, entering in the minutest detail with the same zest as if he had been the stroke oar in the University boats.

At last, they arrived in Auckland.

In one of his letters, he described Auckland as a small seaside town, composed chiefly of roughly built houses, among which the churches stood out with a look that reminded him so much of home.

Patteson finds out that his work as a resident clergyman will be at St. John’s College located in a neighborhood in Auckland. After spending some time there, he hopes to go on his first cruise with Bishop Selwyn.

At present, however, it is essential that he should master the language, and this he will do chiefly by constant contact with the Maori people at St. John’s.

Patteson And The Maori People

His daily interaction with the natives drew Patteson into deeper sympathy with them.

In teaching them the truths of the Bible and Christian doctrine, he found them apt scholars, ready with questions, which showed their intelligent interest in the subject at hand.

His incredible gift of language made Patteson very popular.

He was so thorough in studying the niceties of the dialect and so patient in acquiring every chance, word, or expression, which might qualify him more completely for preaching, that the Maori people begged him to stay when he was about to leave the islands.

Patteson In Vanuatu

With intense anticipation, he waited for the day when he should sail with Bishop Selwyn and cruise the isles of Melanesia.

That moment came at last in May 1856, when Patteson was 29.

The trim little schooner Southern Cross waited for them, and the party went on board on May 1, the feast day of the Solemnity of the Ascension of the Lord.

The passengers included Bishop Selwyn and his devoted wife; Mr. Harper; a son of the future Bishop of Lyttelton; Patteson; and five men to act as crew.

There they visited two noble missionaries, John Geddie (1815-1872) and John Inglis (1808-1891) and witnessed their excellent work, which they carried out for years under the auspices of the Scottish Presbyterian Missionary Society.

The ship sailed again, passing Erromango, another island in Vanuatu and the place of the martyrdom of English missionary John Williams (1796-1839).

They arrived at Efate, an island of very evil repute, as the natives were cannibals, who murdered their Samoan teacher.

Landing there was out of the question, but from the canoes that surrounded the ship, they took two fellows to accompany them on the cruise.

Shortly afterwards, they came in sight of the magnificent ranges of mountains, which rise 4,000 feet on the island of Espiritu Santo (Holy Spirit).

The aspect of these beautiful tropical gems of the ocean greatly pleased the eye of the new missionary.

To Patteson, whose mind was quick to appreciate the artistic beauty of such a scene, the glow of pleasure, which flushed him, would pale down as the stern reality of the shadow demanded the utmost heroism of his soul.

Confronting Challenges

Amid the wild solitude of Africa, Scottish Christian missionary and African explorer Dr. David Livingstone (1813-1873) learned that other white men, guided by an Arab slave trader, preceded him.

Step by step, this intrepid doctor-explorer had to battle with the “white enemies” of the Africans.

It was this vile slave trade which blighted those African villages.

From this noble heart, Patteson prayed that other people might help “to heal this open sore of the world.”

In like manner, he was forestalled by the same vicious influence, and eventually paid the forfeit of his life in his endeavors - all in the name of God - to win the wronged confidence of the Melanesians.

The distrust engendered among the natives made the visits of the missionaries to these islands very perilous, and on many occasions, Patteson barely escaped with his life.

Others Islands

Patteson and his companions, aboard the Southern Cross, reached Guadalcanal, an island in the Solomon Islands.

Immediately, several natives leapt into the sea and swam towards the ship, bringing with them yams and other produce for barter.

The absence of arms showed that their intentions were friendly, and many natives were allowed to come on deck.

The natives that Patteson saw seemed to have come from a rather aristocratic race. They were adorned with fantastic arrangements of shells, frontlet, girdles, and bracelets extending far up the arm.

In addition, although not tattooed like the other islanders, they had branded their skin in a peculiar fashion.

Fortunately, the boys from Bauro, a municipality in Brazil, could talk a little to these natives, and two young men were persuaded to remain with the ship.

The Southern Cross continued to sail and, at the beginning of September, arrived in Nengone (Maré Island), an island in New Caledonia.

On this island, the Melanesian Mission had already begun settlement work.

There, Patteson wrote letters to his relatives at home.

After recounting the incidence of this his first voyage, after visiting 66 islands and landing 81 times, he assured his family that all the locals were most friendly and delightful.

He added that they experienced being shot with arrows, with one arrow barely missing him.

This first voyage was full of meaning to Patteson.

It enriched him with experience and inflamed him with an increasing devotedness to his work.

He wasn’t in such good health as when he started, not to mention, an inflamed leg gave him much uneasiness.

Nevertheless, Patteson was glad to return to St. John’s College in Auckland, with his new consignment of native youths to train and teach for Christ.

Once more, the Southern Cross set her sails to the breeze and, carrying Bishop Selwyn and Patteson, steered for the group of islands of the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu).

Priests from the Roman Catholic Church were imported into the midst of these people, and, backed up with men-of-war afloat and the soldiers ashore, they endeavored to make converts by coercion.

It has been seen that wherever Bishop Selwyn and Patteson traveled on their missionary work, they found themselves in cordial sympathy with the works of other Protestant Christians.

However, the Roman Catholic Mission would have no fellowship with them and persisted in opposing them everywhere.

For over three weeks, Patteson lived in Lifou, an island in New Caledonia, where he taught 25 young men.

Then, together with British Anglican minister and missionary Benjamin Yate Ashwell (1810-1883) and other people including native scholars, they sailed to Erromango in Vanuatu.

Scottish-Canadian missionary Reverend James Douglas Gordon (1832-1872) welcomed them to the island.

Just about this time, Patteson wrote in one of his letters that according to his father’s tutor:

“„There must be a Melanesian Bishop soon, and that you [Patteson] will be the man.- from the tutor of Sir John Patteson (1790-1861)

Patteson wrote that it’s a “a sentence which amuses [him] not a little.”

Pattenson - A Bishop In The Making

But those who had watched his career and his splendid grip upon the work were convinced that Pattenson was the man when the time should come.

Already the question was being mooted at home, the mission had made such strides that the need of more effective organizations and larger support was pressing on the minds of the friends in England.

Anyway, whatever his future status in the work should be, Patteson had fully decided to stand by Melanesia.

His heart was there and the spell of its claims had quite overcome any lingering desire to return to his native land.

Two Losses

On March 26, 1860, five years to the day from the date of his leaving home, Patteson witnessed the death of one of his most faithful converts, a native youth from Nengone (Maré Island).

At his baptism, he was given the name George Selwyn Simeona. He succumbed to the New Zealand winter and passed away.

Just off the coast of New Zealand was a dangerous show of rock, known as the Hen and Chickens Islands. This place was destined to see the loss of that brave little schooner, the Southern Cross.

Patteson, The Bishop

In 1861, Patteson had served six years under the guidance and supervision of Bishop Selwyn, who had, for some time past, left him wholly responsible.

At St. Paul’s Church in Auckland, Patteson became the first Bishop of Melanesia.

His formal installation took place in the little chapel of St. Andrew’s College in Kohimarama in the presence of all his boys.

Afterwards, the new bishop and his young fellows dined together and feasted on roast beef and plum pudding in the College Hall.

The news of Patteson’s consecration had reached home and filled the household at Feniton, a village in England, with a thrill of satisfaction.

New Missions As A New Bishop

Bishop Patteson’s own health was beginning to lose ground; yet, he gladly accepted the offer of Captain Francis Alexander Hume (1831-1916) of HMS Cordelia to go for a cruise among the islands of his diocese.

The voyage comprised a visit to the Solomon Islands, particularly in the island of Ysabel (now Santa Isabel Island).

He gave special attention to translating written works into different languages, a task for which he had a special aptitude.

In the fall of 1862, Bishop Patteson went to the New Hebrides (Vanuatu) and other islands in the Solomon Islands.

The inhabitants of the important island of Santa Cruz had an evil reputation for acts of cannibalism and murder, but he eagerly seized the opportunities to visit as many islands as possible to make his face familiar to the natives.

In the summer of 1865, Bishop Patteson again visited Mota, an island in Vanuatu, to carry out his cherished dream of founding a Christian village there.

Declining Health And Death

In 1870, a serious illness compelled Bishop Patteson to take a complete rest.

When he recuperated and returned to Auckland, his graying hair and loss of vitality and the different look on his face all became noticeable.

On September 20, 1871, Bishop Patteson and his party sailed to Nukapu Island, Santa Cruz, in the Solomon Islands.

Their ship stood off the reef and several canoes filled with natives were seen cruising about. Taking with them a few presents, Bishop Patteson and some co-passengers got into a boat and pulled towards the island.

Although the natives recognized him, there was a strangeness in their manner.

To disarm any suspicions they might have, Bishop Patteson went into one of their canoes.

The canoes were now dragged over the reef into the deep lagoon, and the friends of the bishop saw him land and then disappear in the crowd.

With intense anxiety, they waited for his return.

Suddenly, a shower of arrows followed with cries of vengeance.

The shaft flew with fatal accuracy and the boat was pulled back to the ship filled with wounded men.

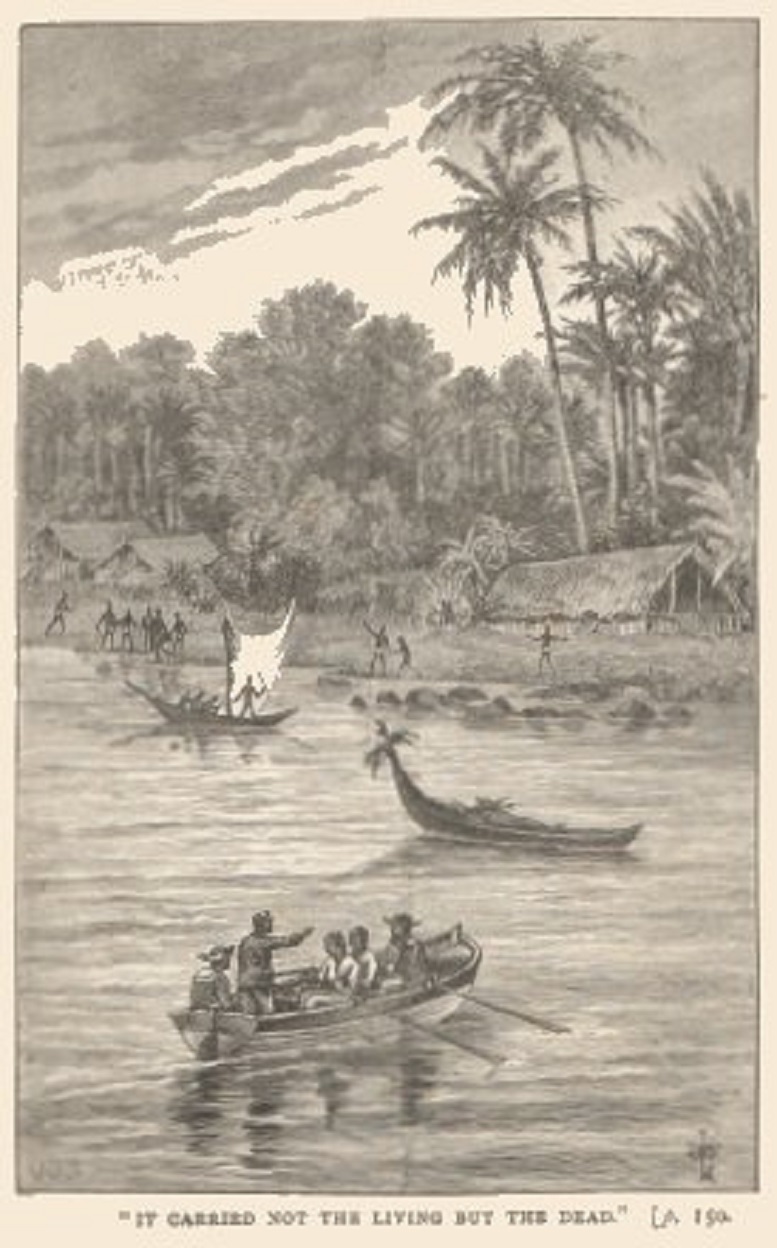

The bishop’s clergyman, Reverend Joseph Atkins (1844-1871), who had been dangerously stuck on the shoulder, insisted at once on returning to look after Patteson.

The native boys and two sailors quickly volunteered to accompany him.

As the tide rose, their boat was able to cross the reef.

Two canoes were being rowed to meet them; one shortly went back, leaving the other canoe to float forward. In it was a heap.

One of the sailors, thinking it might be a man in ambush, prepared his pistol.

But it carried not the living but the dead - the lifeless body of Bishop Patteson.

It was wrapped carefully in a native mat. Upon the breast was placed a spray of native palm, with five mysterious knots tied in leaves.

When they unwrapped them, beneath the spray of palm, were five wounds.

The explanation of this was that Bishop Patteson had been killed in compensation of the outrage on five natives who had died at the hands of white men who kidnap natives for slave trade.

Rev. Atkins later died because of his injuries.

The next day, they buried Bishop Patteson.

Jump to

Early Influence

Education And Her Mother’s Death

Early Travels

Ministerial Work

The Church In Melanesia

The Voyage To New Zealand

Patteson And The Maori People

Patteson In Vanuatu

Confronting Challenges

Others Islands

Pattenson - A Bishop In The Making

Two Losses

Patteson, The Bishop

New Missions As A New Bishop

Declining Health And Death

Latest Articles

Popular Articles